Identifying People by Their Browsing Histories (Yes, it’s Quite Possible)

Most people don’t pay much attention to their web browsing histories (other than sometimes deleting it so that their significant others don’t see the sites they visit), but that can be a big mistake.

In one of our previous articles, we discussed why it is important to hide your browsing history from your ISP and keep your online activities hidden, but an interesting paper shows that it’s much worse than that.

Yes, They Can Identify You by Your Web Browsing History Patterns

The paper, titled “Replication: Why We Still Can’t Browse in Peace: On the Uniqueness and Reidentifiability of Web Browsing History”, was written in 2020 by Mozilla researchers Sarah Bird, Ilana Segall and Martin Lopatka.

It is a replication and an extension of the 2012 paper by Lukasz Olejnik, Claude Casteluccia and Artur Janc, titled “Why Johnny Can’t Browse in Peace: On the Uniqueness of Web Browsing History Patterns.

The original research paper gathered web browsing history from 368,284 Internet users and showed that for more than two-thirds (69% ), their browsing histories were unique and in 97% the researchers were able to uniquely identify at least 4 websites they visited.

Furthermore, in 38% of cases of repeat visitors, their browsing history fingerprints were identical over time, indicating they had pretty static browsing preferences.

The researchers were also able to fingerprint 42% of users based on testing 50 web pages, while that percentage increased to 70% with 500 pages tested.

Here is the abstract of the original research paper:

We present the results of the first large-scale study of the uniqueness of Web browsing histories, gathered from a total of 368, 284 Internet users who visited a history detection demonstration website. Our results show that for a majority of users (69%), the browsing history is unique and that users for whom we could detect at least 4 visited websites were uniquely identified by their histories in 97% of cases. We observe a significant rate of stability in browser history fingerprints: for repeat visitors, 38% of fingerprints are identical over time, and differing ones were correlated with original history contents, indicating static browsing preferences (for history subvectors of size 50). We report a striking result that it is enough to test for a small number of pages in order to both enumerate users’ interests and perform an efficient and unique behavioral fingerprint; we show that testing 50 web pages is enough to fingerprint 42% of users in our database, increasing to 70% with 500 web pages. Finally, we show that indirect history data, such as information about categories of visited websites can also be effective in fingerprinting users, and that similar fingerprinting can be performed by common script providers such as Google or Facebook.

Okay, back to the 2020 paper. This paper took two weeks of browsing data from approximately 52,000 Firefox users and identified 48,919 distinctive profiles, 99% of which were unique.

This uniqueness held even when browsing histories were cut to only 100 top websites. The researchers also found that, for users who visited 50+ different domains in the two-week data collection period, about half (50%) could be reidentified using the top 10,000 websites and this reidentifiability went up to more than 80% when users browsed 150+ distinct domains.

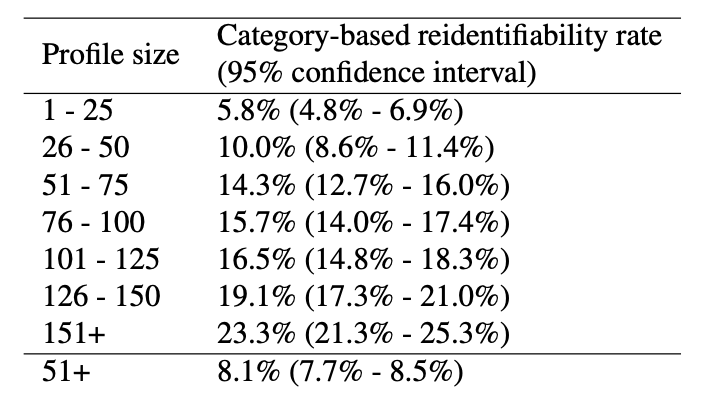

Here is a table showing the reidentifiability rates based on the user profile size:

An abstract from the new, 2020, paper:

We examine the threat to individuals’ privacy based on the feasibility of reidentifying users through distinctive profiles of their browsing history visible to websites and third parties. This work replicates and extends the 2012 paper Why Johnny Can’t Browse in Peace: On the Uniqueness of Web Browsing History Patterns. The original work demonstrated that browsing profiles are highly distinctive and stable. We reproduce those results and extend the original work to detail the privacy risk posed by the aggregation of browsing histories. Our dataset consists of two weeks of browsing data from ~52,000 Firefox users. Our work replicates the original paper’s core findings by identifying 48,919 distinct browsing profiles, of which 99% are unique. High uniqueness holds even when histories are truncated to just 100 top sites. We then find that for users who visited 50 or more distinct domains in the two-week data collection period, ~50% can be reidentified using the top 10k sites. Reidentifiability rose to over 80% for users that browsed 150 or more distinct domains. Finally, we observe numerous third parties pervasive enough to gather web histories sufficient to leverage browsing history as an identifier.

Comments from the Original Paper’s Author on the New Paper and the Uniqueness of Web Browsing Histories

One of the authors of the original paper, Lukasz Olejnik, commented on the findings made by the Mozilla team in 2020. What’s interesting is that, although separated by a decade, the two papers came up with almost the same results and conclusions when it comes to identifying people by their browsing histories.

In an article titled “Web Browsing Histories are Private Personal Data – Now What?”, Olejnik said:

It turns out that our initial indicative work is now significantly upheld by recent (2020) research from Mozilla (by Sarah Bird, Ilana Segall and Martin Lopatka) that has replicated our original study, using very refined data. This work provides an even more stringent assessment of how sensitive the list of user-visited sites really is. The case is stronger, which should be a call to action to many.

You can read the article by Olejnik, here.

He also points out that web browsing histories are very sensitive data and that they provide a lot of information about the user, to the point of being unique to the user.

This is because users, in general, tend to browse a specific set of websites based on their own interests over and over again. For example, you might be interested in technology so you’ll likely browse tech sites more than other types.

According to Olejnik:

In some ways, browsing history resemble biometric-like data due to their uniqueness and stability.

Now, if you know anything about biometric authentication technology, you know that it has its own dangers, as we explained in this article on the pros and cons of BAT.

Olejnik, quite correctly points out that, if data can be singled out to a unique individual (and both papers showed that it can) then it automatically falls under GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation).

According to GDPR’s section on Personal Data:

The data subjects are identifiable if they can be directly or indirectly identified, especially by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or one of several special characteristics, which expresses the physical physiological, genetic, mental, commercial, cultural or social identity of these natural persons. For example. the telephone, credit card or personal number of a person, account data, number plate, appearance, customer number or address are all personal data.

And now we can add their web browsing history patterns to the mix as well.

Conclusion

Web browsing history is often neglected in discussions about data privacy, but as these two papers and several of our articles (including the one on the dangers of browser fingerprinting), this data can be used to identify and track you and therefore shouldn’t be neglected.